Galya Dimitrova

Getty Images

Getty ImagesA university exhibition showing Jane Austen's time living in Oxford has opened.

The Austens at Oxford, which is on display at St John's College Kendrew Barn until 8 December, features letters, objects and stories from the family's time in the city.

It is part of a year of events marking the 250th anniversary of the writer's birth.

Co-curator Michael Riordan, archivist at the college, said he believed it had been the biggest Austen artefacts exhibition in the city during the anniversary.

The college said nearly all of Jane Austen's close and extended family had strong ties to the University of Oxford.

"The founder of St John's College was Sir Thomas White, who died in 1567, but Jane is a direct descendant of his sister, making her the seven times great niece of the founder of St. John's College," Mr Riordan said.

"There were, in fact, four generations of the Austen family who were fellows of the college."

Jane Austen herself went to school in Oxford in 1783, at seven-years old.

St John's College, Oxford

St John's College, OxfordCo-curator Dr Timothy Manningmore said the writer's time at Oxford had been "brief and also not the happiest".

"The kind of tone she talks about Oxford is very satiric and ironic," he said.

Dr Manningmore said a lot of the good and bad characters in her novels went to Oxford and "seem to have kept their character despite being here".

"And you do get the sense that her brothers, James and Henry Austen, really loved their time here," he said.

"Even though they weren't as wealthy as many of the other students here, you do get the sense that they managed to integrate and have a really great time."

Mr Riordan said one of his favourite pieces in the exhibition was evidence of what Austen's father, George, ate in the college hall.

He said: "One we've got on display shows his dinner one evening that includes quite innocuous things like fish and sauce and gooseberry pie and lemons, but then he's also eating tongue and udder, which was a popular 18th Century dish.

"We've also got two copies of The Loiterer magazine where you can read what is arguably the piece by Jane Austen herself, talking about the dismal halls and the dusty libraries."

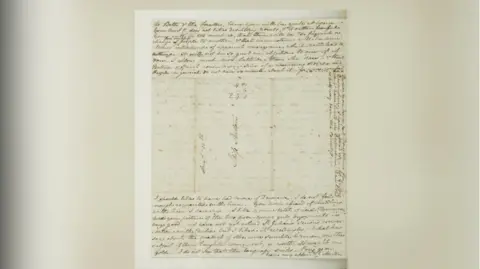

Dr Manningmore said the letters on display were "genuinely a treasure" as they were "so extraordinarily rare".

"She's often very insulting and funny and nearly every single one of her letters was burnt after she died because of that reason, so less than one percent of her letters are thought to survive," he said.

"The fact that we have a folio of five letters is really special."

St John's College, Oxford

St John's College, Oxford